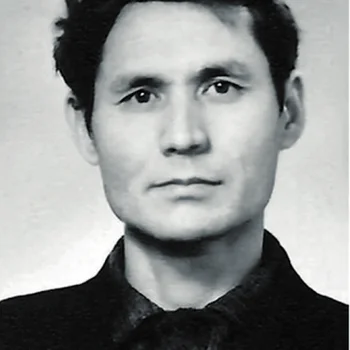

Bozov Nurbek Safievich

Rising above the bustle

Few at the university already remember this tall, fit man, who was distinguished even by his outwardly unusual appearance, seemingly soaring, towering above the everyday bustle. Nurbek Safievich Bozov (1935-2001) – Doctor of Philosophy, Professor, Head of the Department of Philosophy at the Kokchetav Pedagogical Institute – originally from the Zelenovsky, now Baiterek district of the West Kazakhstan region. The life credo of an unusual personality, a graduate of the Faculty of Philosophy of Sverdlovsk State University, would be suited to the formula of the philosopher Merab Mamardashvili: “Man is the effort to be a man.” Philosophical works are the therapy of the soul. Studying them, a thoughtful person seems to be passing through a stream of sunlight and gaining vital energy. In 1997, a graduate of Kazan University, Gulmira Toktarovna Karimova, now deputy of the Department of Internal Policy of the Akmola Region, appeared at the department headed by Bozov. The young teacher’s first impression of his supervisor was his piercing, sharp gaze, which seemed to penetrate deep into the interlocutor. “It was difficult for Nurbek Safievich to like him,” shares Gulmira Toktarovna, but if a person turned out to be nice to him, mentally close, he became like-minded. Bozov did a lot for the formation and recognition of the importance of philosophy as a science in a single university. The magic of his personality was such that he made students of various, and non-humanitarian, specialties sincerely fall in love with this difficult and complex mysterious science. He attracted a philosophical view of the world, an amazing gift for understanding simple things filled with the depth of thought.” Nurbek Safievich was distinguished by a certain natural detachment of a thinking scientist, an intellectual. This was a separate person in whom there was not a drop of falsehood. Smart, spiritual nature. His otherness, his special internal autonomous world, read in his gaze, was striking. It would seem that this extraordinary person is not at all affected by the vanity of vanities. He was a truly talented scientist with a complex personality. Ascetic in everyday life, impractical in the everyday sense, not attaching importance to the external side of phenomena. He and his wife raised two daughters and lived in a modest two-room Khrushchev house, without demanding awards or recognition of their undeniable merits. A man of ideas, who did not compromise on principles, who did not exchange the dignity of a true wise scientist for earthly goods. Dignity, physically felt in behavior, in actions, actions and statements, attracted young people to him. He knew his worth, but did not seek confirmation of this; he was of little interest in recognition from management. The following episode is symptomatic: when the rector entered the department, everyone present had the habit of standing up to greet the leader. But Nurbek Safievich never did this, remaining in his place. They approached him, expressing respect, and extended their hand. In today's world, which sometimes resembles a looking-glass with double standards, it is unthinkable for an honest person to compromise, sacrificing something in his integrity. There was not a drop of fat in Nurbek Safievich, this calling card of the weakness of human flesh and the depravity of the human spirit. He could, like no one else, console and encourage his colleagues in a fatherly way; he found the right words of warm participation and support when some of them had a difficult time, understanding the inevitability of drama in the life and fate of every person. It was thanks to the professional and human authority of Nurbek Safievich Bozov that the philosophy department remained for a long time the leading authoritative department of the university, and the teaching of philosophical disciplines for future teachers was significantly strengthened. Many students became seriously interested in philosophical disciplines, studied new research in complex science, and engaged in independent research under the guidance of teachers. Gulmira Rustemovna Sheryazdanovna, now a candidate of political sciences, associate professor at KATU named after Saken Seifullin, returned to her native Kokshetau in 1993 after graduating from Leningrad (St. Petersburg) State University. In her memory, Bozov remained a wise head of the department: “I studied in absentia at the graduate school of the Institute of Philosophy and Law of the Academy of Sciences. It was a difficult time for Kokshetau: interruptions in light and heat, delays in salaries, and it was very cold during classes in the university classrooms. Nurbek Safievich greeted me, a young philosophy teacher, favorably. In the early 90s, education in the Kazakh language was intensively introduced, and Nurbek Safievich, a young specialist who graduated from a Russian university, offered to teach lectures and seminars in the Kazakh language; my national dignity did not allow me to disagree. My mother, a teacher of the Kazakh language and literature at the Kazakh boarding school, Orynsha Seitovna, an excellent student of education in the Kazakh SSR, helped me in my work. Bozov was very pleased with my teaching of philosophy in my native language, warmly commenting on my enthusiasm “you took the bull by the horns.” The then rector Abai Akhmetgalievich treated our department head Nurbek Safievich with great respect, highlighting the honesty, integrity, and depth of knowledge of the great scientist-philosopher.” A deeply decent man who did not betray his moral principles, he cultivated the personality of young teachers and his students without excessive mentoring and edification, but only through the examples of his actions. “Educate and train, but start with yourself first.” He taught me the ability to openly express my civic position without fear, to defend my own opinion without beating around the bush. Teaching philosophical disciplines is a serious, energy-intensive intellectual activity that requires not only knowledge and skills, but also a certain constitution of the psyche. The mentor leaves a lot of physical and mental strength to the audience, but the result is obvious. The scientist Bozov was interested in the theory and history of managerial relations; Nurbek Safievich deeply explored the problems of philosophical and political analysis of managerial relations in the system of social relations. At seventy-two years old, in 1997, Nurbek Safievich defended his doctoral dissertation. Moreover, consciously at a fairly mature age, because he was never in a hurry, did not rush to overtake his colleagues in successes and achievements, did not compete, but threw all his strength on the altar of science itself. He preferred to devote his strength and energy to the formation and development of methods of teaching philosophy and other humanities at the university. It was obvious to everyone around: for Nurbek Safievich the priority was not personal merits and his own scientific achievements, but the work of the department that he headed. The demanding leader gave each of the young teachers a starting opportunity to engage in science. His charges were under the reliable wing of their authoritative scientist in the scientific circles of the republic and achieved success largely thanks to his help and support. Subsequently, it was Gulnazia Zhylkibaevna Esmagulova, faithful to the memory of her beloved leader, who held “Bozov readings” at the university. They say that a true philosopher strives all his life to recognize the riddle of the “philosopher’s stone”: listen to everyday things, listen, you will learn a lot, listen to the wet cloaks and shoes walking along the roads... One day a student asked the Master: “How long will it take to wait for changes for the better?” ?. “If you wait, it will be a long time,” answered the Teacher. Nurbek Safievich Bozov, a thinker, a creator by nature, harmoniously combining the eternal breath of deep philosophical thought with a modern heightened perception of rapid dynamic time, the wind of change, taught, despite the circumstances, despite the adversity of fate, to believe in yourself, in your strengths, remaining a man of Good and Light.